~ Section 2 ~ Officers, Cadets, Training & Buildings ~

~ 01 Entrance Gates of Shotley Barracks, Suffolk (1914) H.R. Tunn H&D ~

~ 02 Entrance Gates of H.M.S. Shotley, Suffolk (1948) H&D ~

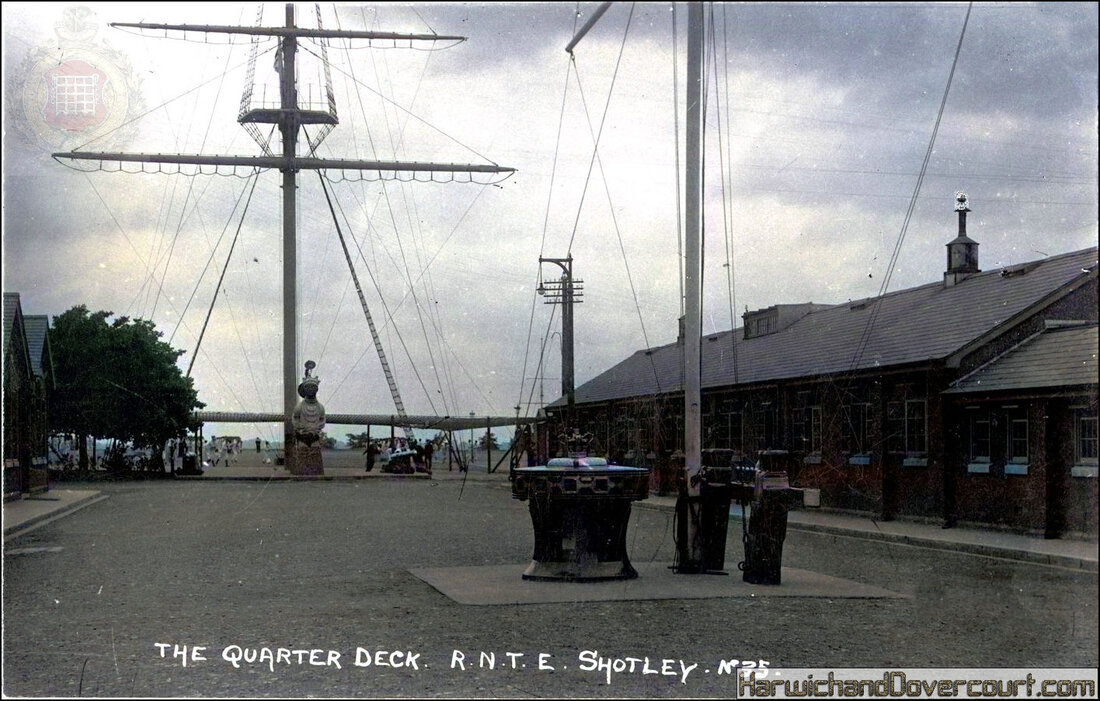

~ 03 No 35 The Quarter Deck R.N.T.E. Shotley (1912) F.Driver H&D ~

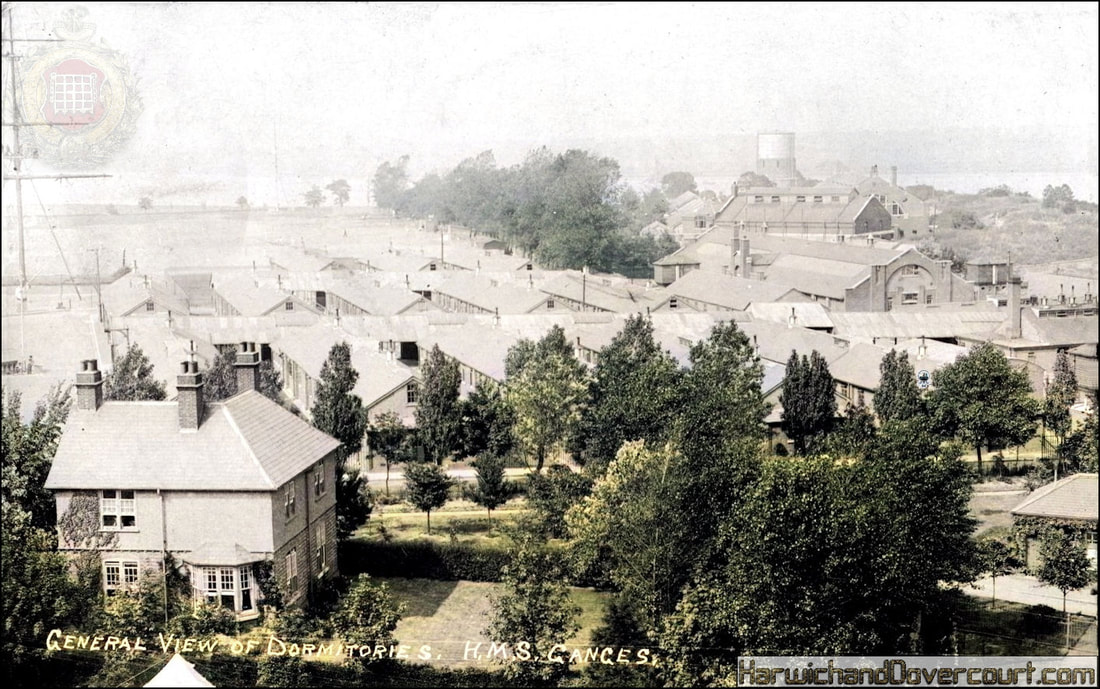

~ 04 General View of Dormitories H.M.S.Ganges (1910) H.R. Tunn H&D ~

~ 05 H.M.S. Ganges, Shotley, Suffolk (1969) H&D ~

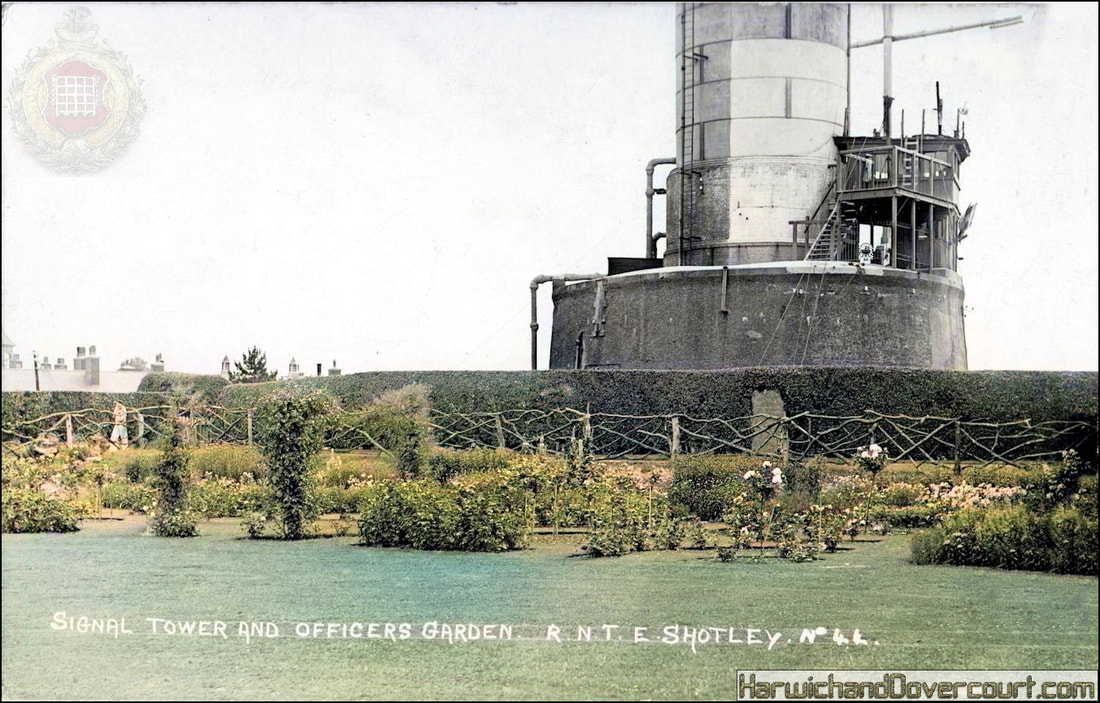

~ 06 No 44 Signal Tower & Officers Garden R.N.T.E. Shotley (1918) H&D ~

~ 07 The Quarter Deck R.N.T.E. Shotley (1908) H&D ~

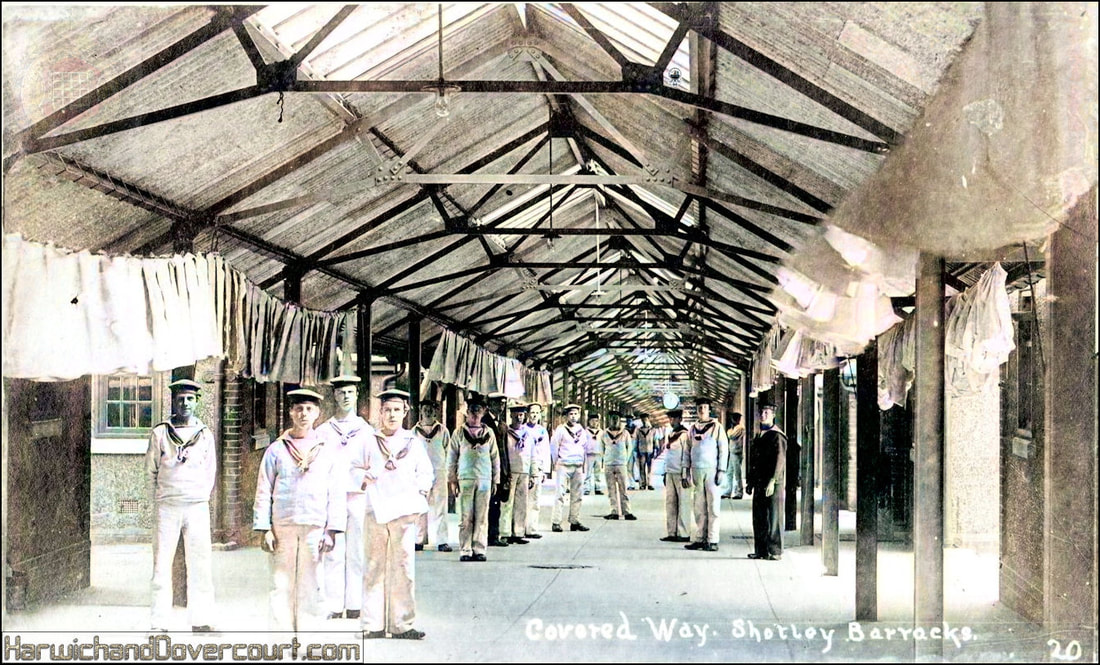

~ 08 #20 Covered Way. Shotley Barracks (1908) H&D ~

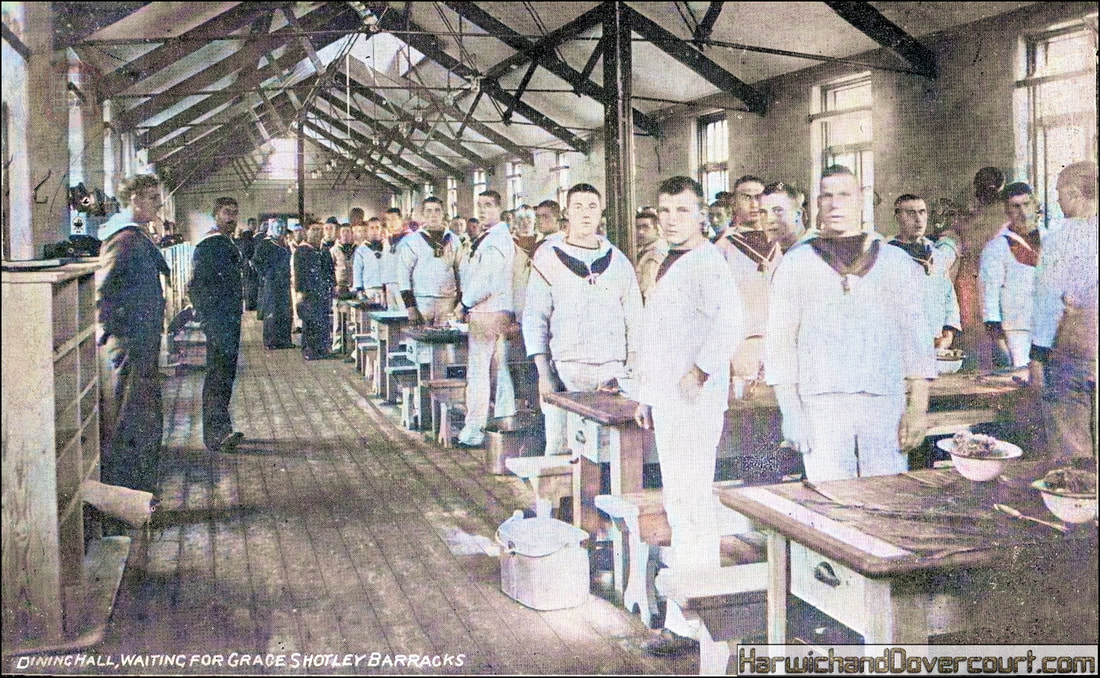

~ 09 Dining Hall, Waiting For Grace, Shotley Barracks (1908) H&D ~

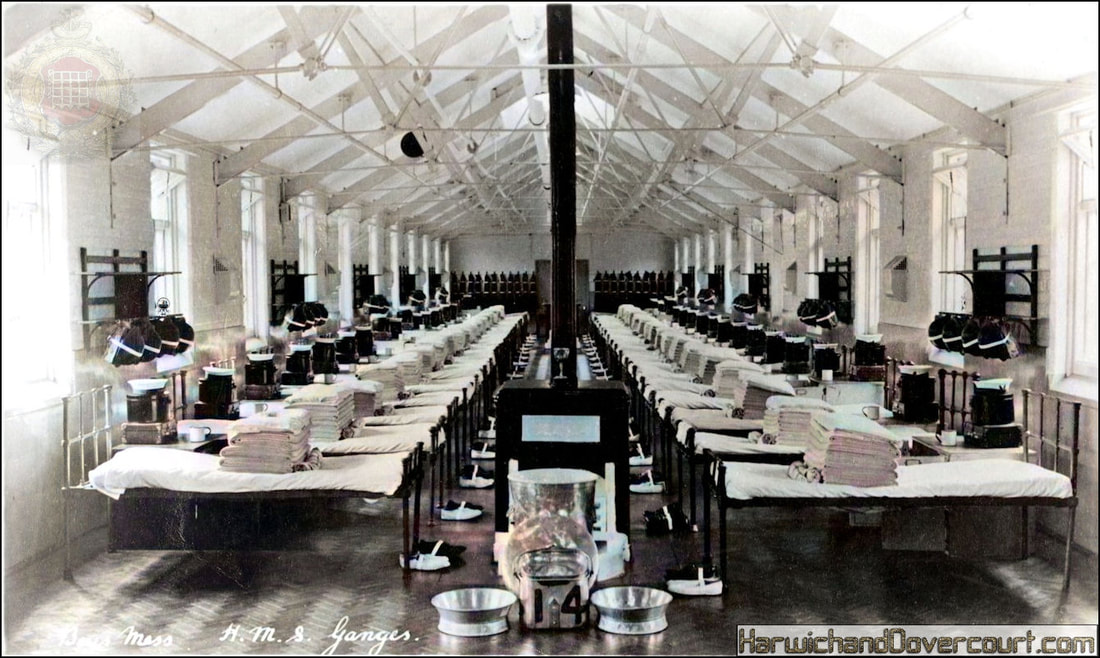

~ 10 Boys Mess. H.M.S. Ganges (1952) H&D ~

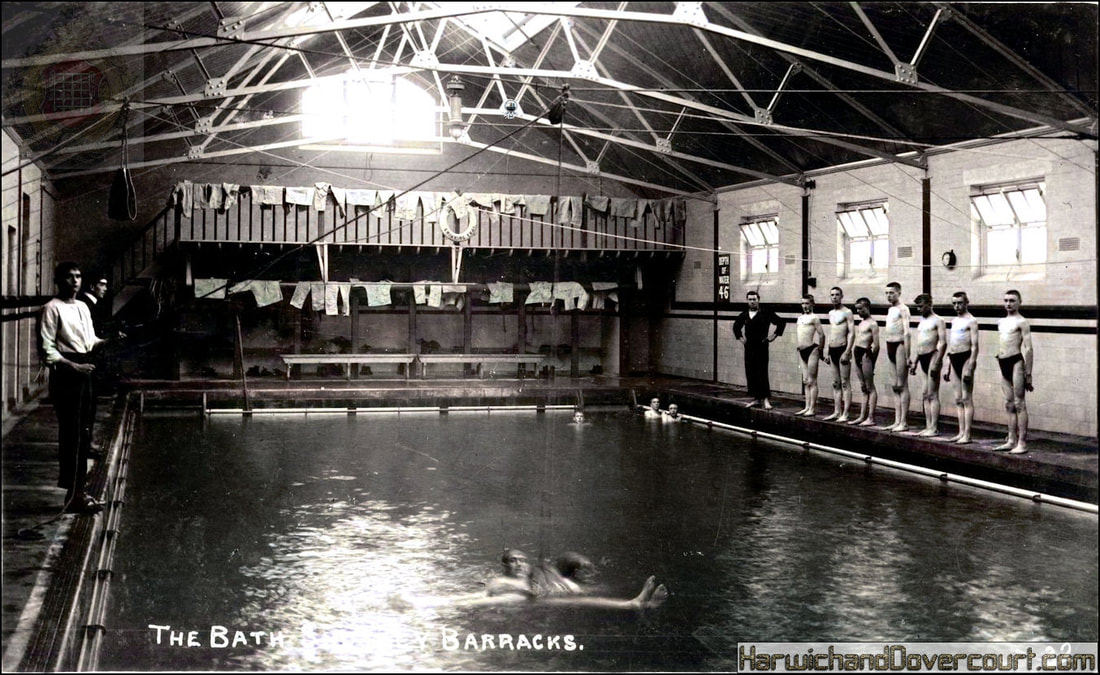

~ 11 HMS Ganges Swimming Bath's (1959) H&D ~

~ 12 #32 The Bath Shotley Barracks (1912) H&D ~

~ 13 #5 Where the "Lads" are taught to shoot (1908) H&D ~

~ 14 Gun Drill, Shotley (1912) H&D ~

~ 15 H.M.S. Ganges Firing Party (1910) H&D ~

~ 16 H.M.S. Ganges Rifle Practice (1911) H&D ~

~ 17 B Class R.N.T.E. Shotley (1912) H&D ~

~ 18 A3 Class H.M.S. Ganges (1913) H&D ~

~ 19 A3 Class H.M.S. Ganges (1913) H&D ~

~ 20 H.M.S. Ganges Passing Out Celebrations (1940) H&D ~

~ 21 H.M.S. Ganges Boxing Team (1950) Edith F. Driver H&D ~

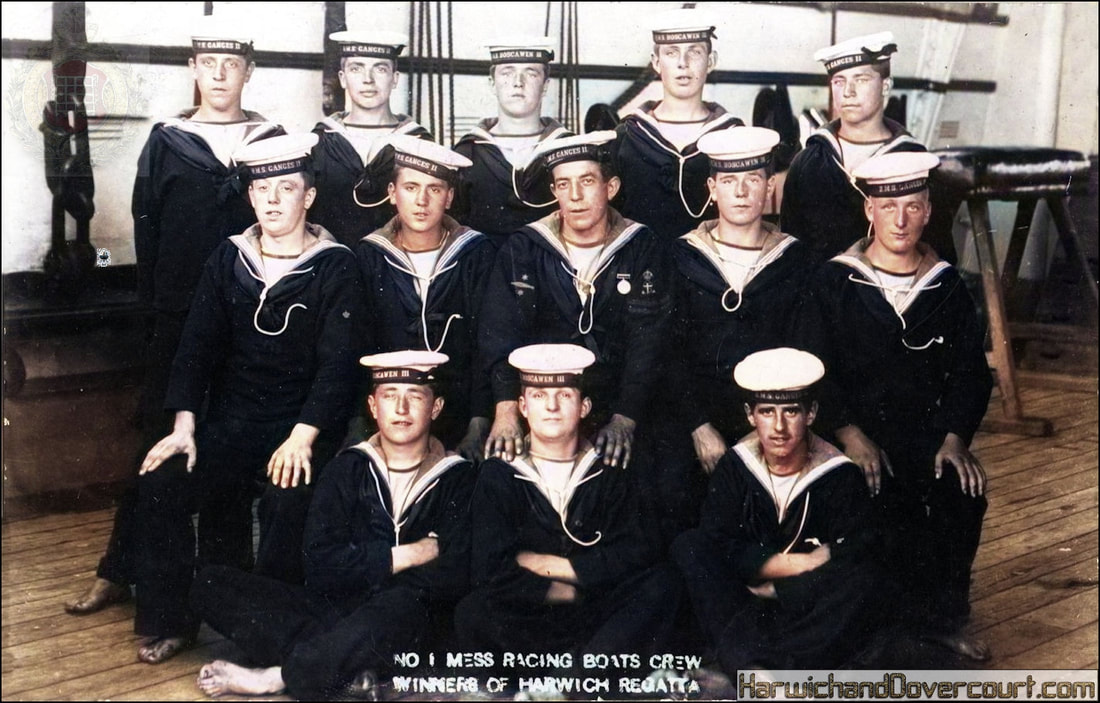

~ 22 No 1 Mess Racing Boats Crew, Winners of Harwich Regatta (1906) Tunn & Co H&D ~

~ 23 HMS Ganges Football Team, with H&D League Winners Cup (1911) H&D ~

~ 24 Royal Marines (Shotley) Football Team (1925) H&D ~

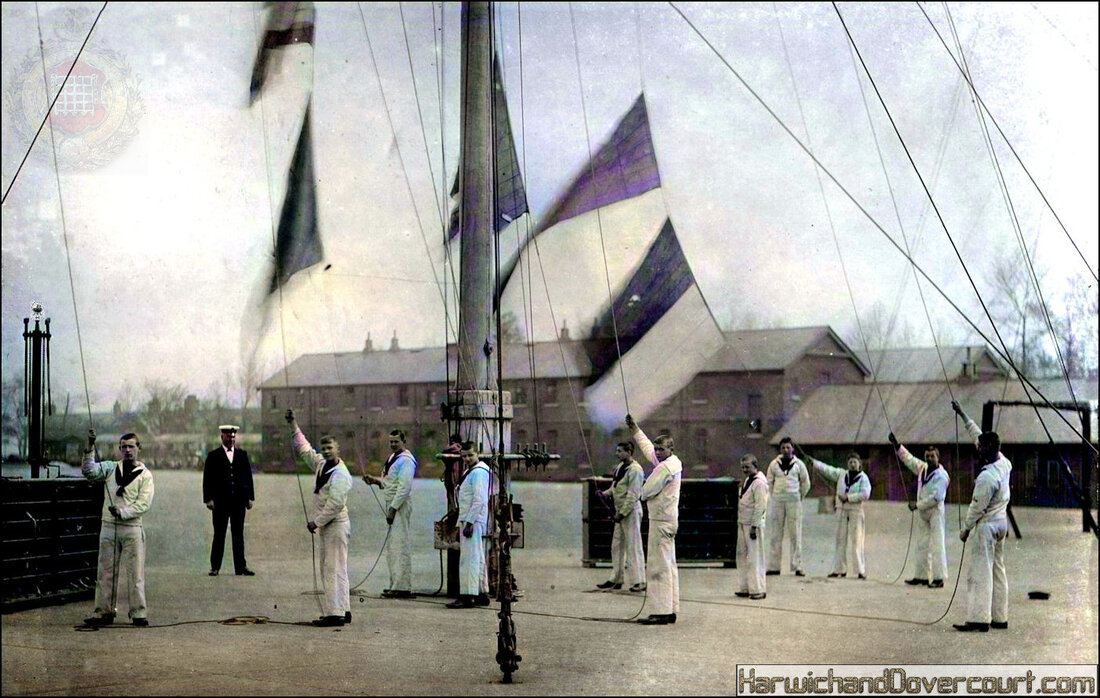

~ 25 Raising The Colours at HMS Ganges (1906) H.R. Tunn ~

~ 26 Climbing The Mast (1955) H&D ~

~ 27 Unknown Funeral Carriage Procession (1919) H&D ~

~ 28 Funeral of H.M.S. Amphion Victims (1914) H&D ~

Funeral of H.M.S. Amphion Victims, part of the Harwich Force (1914)

On the 6th August 1914 one hundred and ten years ago today, the Royal Navy suffered its first loss of the Great War – just hours after its first triumph of the conflict. More than two weeks before the British Expeditionary Force lost its first soldier on the fledgling Western Front; some 130 souls were killed when HMS Amphion sank in the North Sea with the European war barely 30 hours old.

H.MS. Amphion, the second of three Active-class ‘scout’ cruisers – small, lightly-armed and armoured, but relatively fast and agile, serving as the eyes of the Fleet – had only been in service 18 months, assigned to the Harwich Force as one of the guardians of the southern North Sea, Thames Estuary and approaches to the Strait of Dover. On Wednesday August 5, Amphion left Harwich to sweep the North Sea with a destroyer flotilla. Already at sea by the time the British force headed out was a former North Sea ferry, Königin Luise, determined to drop mines to block the shipping lanes to Britain’s capital.

Late in the morning of the fifth – and having already laid a considerable number of ‘eggs’ – the German ferry was spotted and intercepted by destroyers Landrail and Lance, whose 4in guns fired the first British shots of the conflict. When Amphion entered the fray, more than 15 4in guns were pummelling the German steamer, which rolled over after a couple of hours. Amphion moved in to pick up survivors – true to Nelson’s maxim of “humanity after victory” – and rescued 56 of the 130 men aboard, before the force continued its patrol.

The ships soon found fresh pickings. Another steamer, very similar to the makeshift mine layer, flying the Reichskriegs flagge – the German naval ensign. The destroyers closed in to attack, unaware they were about to send the German Ambassador and his staff to the bottom of the North Sea.

Amphion’s captain, Cecil Fox, realised the mistake and ordered the destroyers to break off. They did not. Fox then steamed in with Amphion, putting himself between his destroyers and the steamer, the St Petersburg, in another act of chivalry. The action over, Fox decided to return to Harwich. In doing so, he sailed across the line of mines laid by the Königin Luise. Shortly before 7am on August 6, the Amphion ran over one.

The results were horrific. The blast tore apart Amphion’s forward section – every man save one on the forward guns was killed, and most of the German prisoners being held in the bow. Just before the explosion, 19-year-old Stoker 1st Class Herbert Street from Lyme Regis had been enjoying a break with his fellow stokers, among them a fellow Lyme Regis native, Thomas Gollop. The latter took rather longer to finish his mug of cocoa than his shipmate. It saved his life. Herbert Street was killed in the blast, Thomas Gollop survived. As for Amphion, she was going down by the bow. Cecil Fox ordered his men to abandon ship and his destroyer to close in to pick up survivors. They did so remarkably calmly and remarkably quickly. Within 18 minutes of hitting the mine, every survivor had been taken off, Fox the last man off. The lifeless ship continued to float – and to move.She drifted back into the minefield and struck a second mine, triggering her forward magazine and an explosion far more fearful than the first. Debris was flung around the North Sea, hitting some of the rescue boats. A 4in shell crashed on to the deck of HMS Lark, killing two men just plucked from the Amphion, plus a captured German.

More than 130 Britons died in the loss of the three-year-old cruiser, while more than two dozen of the 56 German sailors rescued also perished. Her wreck, on the bed of the North Sea some 30 miles east of Orford Ness, is a protected war grave. The survivors landed at Harwich, according to a newspaper reporter watching them being helped ashore, bore terrible burns – as if they’d been peppered with acid. “The scene here is like that which follows a colliery explosion.”

The first dead – four British, four German – were buried with full military honours at Shotley Cemetery in Suffolk on August 8 1914.

Such casualties would soon be dwarfed by the Empire’s losses in France. But even in the first month of the war, not one day passed without a member of the Naval Service dying – often of illness, a good few men drowned, and most lost their lives in action.

On the 6th August 1914 one hundred and ten years ago today, the Royal Navy suffered its first loss of the Great War – just hours after its first triumph of the conflict. More than two weeks before the British Expeditionary Force lost its first soldier on the fledgling Western Front; some 130 souls were killed when HMS Amphion sank in the North Sea with the European war barely 30 hours old.

H.MS. Amphion, the second of three Active-class ‘scout’ cruisers – small, lightly-armed and armoured, but relatively fast and agile, serving as the eyes of the Fleet – had only been in service 18 months, assigned to the Harwich Force as one of the guardians of the southern North Sea, Thames Estuary and approaches to the Strait of Dover. On Wednesday August 5, Amphion left Harwich to sweep the North Sea with a destroyer flotilla. Already at sea by the time the British force headed out was a former North Sea ferry, Königin Luise, determined to drop mines to block the shipping lanes to Britain’s capital.

Late in the morning of the fifth – and having already laid a considerable number of ‘eggs’ – the German ferry was spotted and intercepted by destroyers Landrail and Lance, whose 4in guns fired the first British shots of the conflict. When Amphion entered the fray, more than 15 4in guns were pummelling the German steamer, which rolled over after a couple of hours. Amphion moved in to pick up survivors – true to Nelson’s maxim of “humanity after victory” – and rescued 56 of the 130 men aboard, before the force continued its patrol.

The ships soon found fresh pickings. Another steamer, very similar to the makeshift mine layer, flying the Reichskriegs flagge – the German naval ensign. The destroyers closed in to attack, unaware they were about to send the German Ambassador and his staff to the bottom of the North Sea.

Amphion’s captain, Cecil Fox, realised the mistake and ordered the destroyers to break off. They did not. Fox then steamed in with Amphion, putting himself between his destroyers and the steamer, the St Petersburg, in another act of chivalry. The action over, Fox decided to return to Harwich. In doing so, he sailed across the line of mines laid by the Königin Luise. Shortly before 7am on August 6, the Amphion ran over one.

The results were horrific. The blast tore apart Amphion’s forward section – every man save one on the forward guns was killed, and most of the German prisoners being held in the bow. Just before the explosion, 19-year-old Stoker 1st Class Herbert Street from Lyme Regis had been enjoying a break with his fellow stokers, among them a fellow Lyme Regis native, Thomas Gollop. The latter took rather longer to finish his mug of cocoa than his shipmate. It saved his life. Herbert Street was killed in the blast, Thomas Gollop survived. As for Amphion, she was going down by the bow. Cecil Fox ordered his men to abandon ship and his destroyer to close in to pick up survivors. They did so remarkably calmly and remarkably quickly. Within 18 minutes of hitting the mine, every survivor had been taken off, Fox the last man off. The lifeless ship continued to float – and to move.She drifted back into the minefield and struck a second mine, triggering her forward magazine and an explosion far more fearful than the first. Debris was flung around the North Sea, hitting some of the rescue boats. A 4in shell crashed on to the deck of HMS Lark, killing two men just plucked from the Amphion, plus a captured German.

More than 130 Britons died in the loss of the three-year-old cruiser, while more than two dozen of the 56 German sailors rescued also perished. Her wreck, on the bed of the North Sea some 30 miles east of Orford Ness, is a protected war grave. The survivors landed at Harwich, according to a newspaper reporter watching them being helped ashore, bore terrible burns – as if they’d been peppered with acid. “The scene here is like that which follows a colliery explosion.”

The first dead – four British, four German – were buried with full military honours at Shotley Cemetery in Suffolk on August 8 1914.

Such casualties would soon be dwarfed by the Empire’s losses in France. But even in the first month of the war, not one day passed without a member of the Naval Service dying – often of illness, a good few men drowned, and most lost their lives in action.

~ 29 Funeral of H.M.S. Amphion Victims I (1914) H&D ~

~ 30 Funeral of H.M.S. Amphion Victims II (1914) H&D ~

~ 31 HMS Shotley Boat Crews (1908) H&D ~

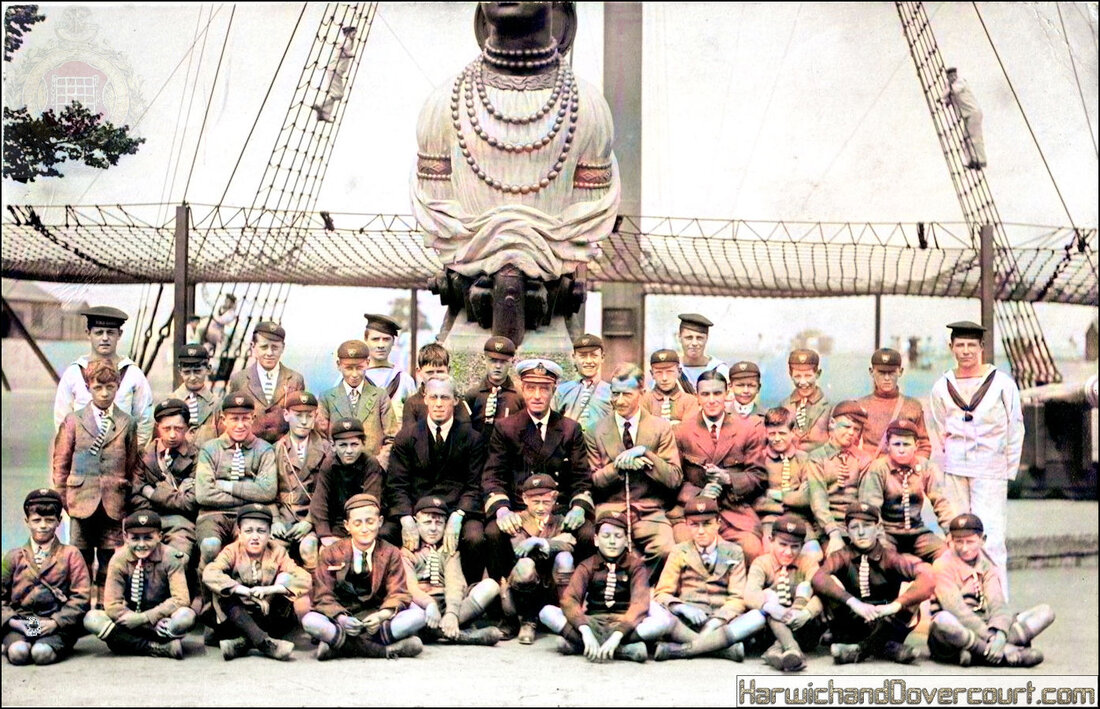

# 32 HMS Ganges School Visit (1922) H&D ~

~ 33 Sir Percy Lockhart Harnam Noble (1909) H&D ~

~ H.M.S. Ganges Training Establishment & Captain-in-Charge, Harwich (1925–1927) ~

Admiral Sir Percy Lockhart Harnam Noble (1880-1955) joined the Navy in 1894.

He first gained recognition on the Royal Yacht HMS Victoria and Albert (1911 – 1913) and as CO he served the Grand Fleet throughout WW1 (1914 –1918) before joining HMS Calliope towards the end of this period.

Promoted Captain in June 1918 he served as Flag Captain on HMS Calcutta (the flagship of Admiral Everett) and was CO aboard HMS Barham within this period ending 1925.

From 1925 until 1927 he was Senior Naval Officer at Harwich and CO at HMS Ganges RN Training Establishment at Shotley.

He then moved to command the boy’s training establishment at Forton, Gosport until 1928.

In March that year he became Director of Operations Division, Naval Staff, Admiralty (HMS President) and achieved promotion to Rear Admiral in October 1929.

In this year he was also Naval ADC to the King.

1931 saw his role change to Director of Naval Equipment (HMS President). He commanded the 2nd Cruiser Squadron (HMS Leander) in late 1932 through to 1934.

He was Lord Commissioner of the Admiralty and Fourth Sea Lord (Chief of Supplies and Transport) from February 1935 gaining promotion to Vice Admiral in May of this year.

From December 1937 until 1940 he was Commander-in-Chief, China Station, HMS Cumberland (02.1938 – 08.1938),

HMS Kent (10.1938 – 08.1939), promoted Admiral in March 1939, HMS Tamar (04.1940).

He was back with HMS President for Miscellaneous Services at the Admiralty from November 1940 to February 1941 before taking up position as Commander-in-Chief, Western Approaches until 1942.

He was Head of the British Naval Delegation, Washington DC, USA 1942 – 1944 and from December of that year until April 1946 returned to HMS President (for Miscellaneous Services at the Admiralty).

From October 1943 until (?) 1945 he was also First and Principle Naval ADC to the King.

He retired as Admiral in 1945 and from June that year until his death in July 1955 held the title Rear-Admiral of the United Kingdom and of the Admiralty.

He first gained recognition on the Royal Yacht HMS Victoria and Albert (1911 – 1913) and as CO he served the Grand Fleet throughout WW1 (1914 –1918) before joining HMS Calliope towards the end of this period.

Promoted Captain in June 1918 he served as Flag Captain on HMS Calcutta (the flagship of Admiral Everett) and was CO aboard HMS Barham within this period ending 1925.

From 1925 until 1927 he was Senior Naval Officer at Harwich and CO at HMS Ganges RN Training Establishment at Shotley.

He then moved to command the boy’s training establishment at Forton, Gosport until 1928.

In March that year he became Director of Operations Division, Naval Staff, Admiralty (HMS President) and achieved promotion to Rear Admiral in October 1929.

In this year he was also Naval ADC to the King.

1931 saw his role change to Director of Naval Equipment (HMS President). He commanded the 2nd Cruiser Squadron (HMS Leander) in late 1932 through to 1934.

He was Lord Commissioner of the Admiralty and Fourth Sea Lord (Chief of Supplies and Transport) from February 1935 gaining promotion to Vice Admiral in May of this year.

From December 1937 until 1940 he was Commander-in-Chief, China Station, HMS Cumberland (02.1938 – 08.1938),

HMS Kent (10.1938 – 08.1939), promoted Admiral in March 1939, HMS Tamar (04.1940).

He was back with HMS President for Miscellaneous Services at the Admiralty from November 1940 to February 1941 before taking up position as Commander-in-Chief, Western Approaches until 1942.

He was Head of the British Naval Delegation, Washington DC, USA 1942 – 1944 and from December of that year until April 1946 returned to HMS President (for Miscellaneous Services at the Admiralty).

From October 1943 until (?) 1945 he was also First and Principle Naval ADC to the King.

He retired as Admiral in 1945 and from June that year until his death in July 1955 held the title Rear-Admiral of the United Kingdom and of the Admiralty.