Smaller Boats, Yachts & Ferries

~ The Douglas Motor Launch - "Harwich To Walton" Route (1923) by Wallis H&D ~

~H.M.S. Hotspur at Harwich Harbour, Essex (1887) H&D ~

HMS Hotspur was a Victorian Royal Navy ironclad ram – a warship armed with guns but whose primary weapon was a ram.

Background

It had been recognised since the time of the Roman Empire or before that a ship, while it might carry weaponry, was itself a potent weapon if used as a missile against other ships. In the era of sail-powered warships with their intrinsic limitations of speed and manoeuvrability the practice of ramming opponents fell by default into disuse, although the concept remained alive. With the advent of steam-powered vessels, with their enhanced speed and lack of dependence for direction on the wind, the ram as a potent weapon of attack gained credibility in Naval circles and in Ship Constructors' departments. This first became apparent in the American Civil War, when many attempts were made by ships on both sides to ram their opponents, with almost uniform lack of success. (The Confederate Virginia (ex-Merrimack) rammed and sank the Federal Cumberland, but lost her ram and suffered significant structural damage.)

The battle which most influenced the exaggerated faith in the ram as a weapon was the battle of Lissa between Austria-Hungary and Italy in 1866. The Austrian Ferdinand Max rammed the (stationary) Italian Re d'Italia, which immediately heeled over and sank. This resulted in all ironclad battleships designed for the next forty years being built to carry a ram; a weapon which, while causing the loss of a number of ships accidentally, never sank another major enemy warship of any nationality.

Design

Hotspur was designed to work with the Fleet, to bring into action her main weapon, her ram. This projected some ten feet (3 m) ahead of her bow perpendicular, and was reinforced by an extension of the armoured belt.

A 12-inch (305 mm) 25-ton muzzle-loading rifle on a broadside mounting aboard Hotspur. The deck beneath the mounting was a turntable which allowed the gun to rotate between several gunports within a fixed circular armored turret. One of the gun's shells is hanging in the gunport in front of the gun.

A rear view of a 12-inch (305 mm) 25-ton gun aboard Hotspur.

It was assumed that the bearings upon which a usual turret turned would not survive the shock of the impact consequent upon the use of the ram against an enemy ship. Her single 12-inch (305 mm) gun was therefore positioned in a fixed cupola perforated by four firing-ports through which the gun could be discharged. None of these ports allowed the gun to be fired straight ahead, where a potential ramming target would be situated. It was therefore only possible to engage these targets with the gun if the ramming attack missed.

As the maximum speed of Hotspur was less than virtually all of her potential targets, it quickly became apparent that ramming attacks on ships under way were almost guaranteed to miss, and she quickly descended from being a ship held to be of great military value to be the most useless member of the battle-fleet.

She was reconstructed by Laird & Sons Co., and was given a revolving turret containing two 12-inch guns, new boilers and additional armour.

Service history

Hotspur was commissioned at Devonport in 1871.[citation needed] On 26 January, she collided with the steamship Lady Woodhouse off Plymouth. Both vessels were severely damaged. Hotspur was taken in to Plymouth for repairs.

Her 12-inch 25-ton gun was fired on the Glatton during a live trial in 1873.

She remained in reserve until 1876. She served with HMS Rupert in the Sea of Marmara during the Russo-Turkish war of 1878. She then returned to Devonport, where she remained until her major reconstruction, undertaken by Laird & Sons Co. between 1881 and 1883. Her only active service thereafter was with the Particular Service Squadron of 1885. She was guardship at Holyhead until 1893, was again in reserve until 1897, and was posted thereafter to serve as guardship at the Royal Naval Dockyard in the Imperial fortress colony of Bermuda, where she stayed until sold.

Background

It had been recognised since the time of the Roman Empire or before that a ship, while it might carry weaponry, was itself a potent weapon if used as a missile against other ships. In the era of sail-powered warships with their intrinsic limitations of speed and manoeuvrability the practice of ramming opponents fell by default into disuse, although the concept remained alive. With the advent of steam-powered vessels, with their enhanced speed and lack of dependence for direction on the wind, the ram as a potent weapon of attack gained credibility in Naval circles and in Ship Constructors' departments. This first became apparent in the American Civil War, when many attempts were made by ships on both sides to ram their opponents, with almost uniform lack of success. (The Confederate Virginia (ex-Merrimack) rammed and sank the Federal Cumberland, but lost her ram and suffered significant structural damage.)

The battle which most influenced the exaggerated faith in the ram as a weapon was the battle of Lissa between Austria-Hungary and Italy in 1866. The Austrian Ferdinand Max rammed the (stationary) Italian Re d'Italia, which immediately heeled over and sank. This resulted in all ironclad battleships designed for the next forty years being built to carry a ram; a weapon which, while causing the loss of a number of ships accidentally, never sank another major enemy warship of any nationality.

Design

Hotspur was designed to work with the Fleet, to bring into action her main weapon, her ram. This projected some ten feet (3 m) ahead of her bow perpendicular, and was reinforced by an extension of the armoured belt.

A 12-inch (305 mm) 25-ton muzzle-loading rifle on a broadside mounting aboard Hotspur. The deck beneath the mounting was a turntable which allowed the gun to rotate between several gunports within a fixed circular armored turret. One of the gun's shells is hanging in the gunport in front of the gun.

A rear view of a 12-inch (305 mm) 25-ton gun aboard Hotspur.

It was assumed that the bearings upon which a usual turret turned would not survive the shock of the impact consequent upon the use of the ram against an enemy ship. Her single 12-inch (305 mm) gun was therefore positioned in a fixed cupola perforated by four firing-ports through which the gun could be discharged. None of these ports allowed the gun to be fired straight ahead, where a potential ramming target would be situated. It was therefore only possible to engage these targets with the gun if the ramming attack missed.

As the maximum speed of Hotspur was less than virtually all of her potential targets, it quickly became apparent that ramming attacks on ships under way were almost guaranteed to miss, and she quickly descended from being a ship held to be of great military value to be the most useless member of the battle-fleet.

She was reconstructed by Laird & Sons Co., and was given a revolving turret containing two 12-inch guns, new boilers and additional armour.

Service history

Hotspur was commissioned at Devonport in 1871.[citation needed] On 26 January, she collided with the steamship Lady Woodhouse off Plymouth. Both vessels were severely damaged. Hotspur was taken in to Plymouth for repairs.

Her 12-inch 25-ton gun was fired on the Glatton during a live trial in 1873.

She remained in reserve until 1876. She served with HMS Rupert in the Sea of Marmara during the Russo-Turkish war of 1878. She then returned to Devonport, where she remained until her major reconstruction, undertaken by Laird & Sons Co. between 1881 and 1883. Her only active service thereafter was with the Particular Service Squadron of 1885. She was guardship at Holyhead until 1893, was again in reserve until 1897, and was posted thereafter to serve as guardship at the Royal Naval Dockyard in the Imperial fortress colony of Bermuda, where she stayed until sold.

02 Harwich Bawley Trawler (19--) H&D F

The Harwich Bawley

A shallow draft, wide beam, cutter rigged fishing vessel used primarily for shrimping in the Thames and Medway estuaries until the early 20th century. Its rig differed from that of the "smacks" because it lacked a boom on the mainsail, so it could be easily furled when working with trawls. The hull featured a sharp water inlet that quickly widened to a fairly wide beam at mast height, and thanks to the powerful hull sections, the bawley could spread her large sails even in a fairly strong breeze.

The name bawley probably derives from the onboard stove with cauldron used to 'bawl' (Essex slang for “boil”) shrimp immediately after they were caught.

The bawleys left each morning for the sea and returned in time to put their catch on the afternoon freight train that carried it to the markets. To do this, they were equipped with a winch and a strong manual windlass that made it possible to unload the catch on land anywhere in the port.

Length: 11.60 m.

Beam: 4.0 m.

Draft: 1.50 m.

Mast height from deck: 15.20 m.

A shallow draft, wide beam, cutter rigged fishing vessel used primarily for shrimping in the Thames and Medway estuaries until the early 20th century. Its rig differed from that of the "smacks" because it lacked a boom on the mainsail, so it could be easily furled when working with trawls. The hull featured a sharp water inlet that quickly widened to a fairly wide beam at mast height, and thanks to the powerful hull sections, the bawley could spread her large sails even in a fairly strong breeze.

The name bawley probably derives from the onboard stove with cauldron used to 'bawl' (Essex slang for “boil”) shrimp immediately after they were caught.

The bawleys left each morning for the sea and returned in time to put their catch on the afternoon freight train that carried it to the markets. To do this, they were equipped with a winch and a strong manual windlass that made it possible to unload the catch on land anywhere in the port.

Length: 11.60 m.

Beam: 4.0 m.

Draft: 1.50 m.

Mast height from deck: 15.20 m.

~ Harwich Lifeboats (1920) H&D ~

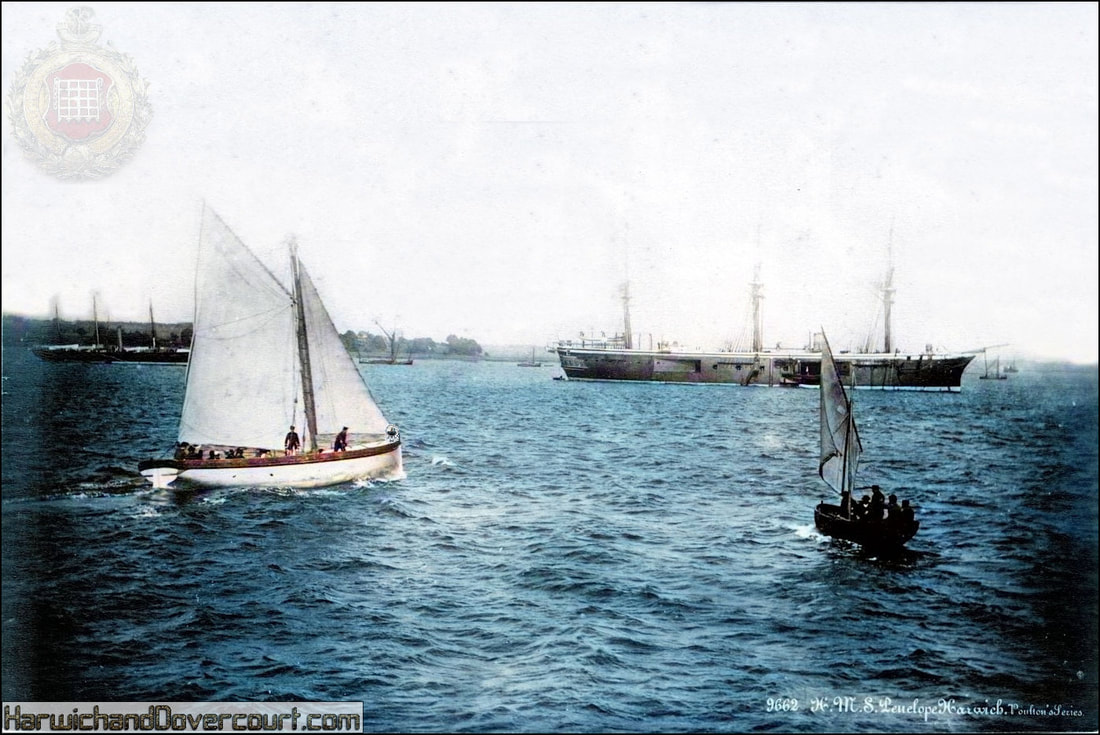

~ #9662 H.M.S. Penelope, Harwich (Aug 31st 1887) Poulton Series H&D ~

HMS Penelope was a central-battery ironclad built for the Royal Navy in the late 1860s and was rated as an armoured corvette.

She was designed for inshore work with a shallow draught, which severely compromised her performance under sail. Completed in 1868, the ship spent the next year with the Channel Fleet before she was assigned to the First Reserve Squadron in 1869 and became the coast guard ship for Harwich until 1887. Penelope was mobilised as tensions with Russia rose during the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78 and participated in the Bombardment of Alexandria during the Anglo-Egyptian War of 1882. The ship became a receiving ship in South Africa in 1888 and then a prison hulk in 1897. She was sold for scrap in 1912.

Design

The chief constructor, Sir Edward Reed, was ill, so the design of this ship was entrusted to his assistant and brother-in-law, Nathaniel Barnaby, himself a future chief constructor. For reasons that have not survived, the Admiralty required that Penelope to be a ship of unusually shallow draught, possibly in light of the operations in the shallow Baltic Sea during the Crimean War of 1854–1855.

The ship was 260 feet (79.2 m) long between perpendiculars and had a beam of 50 feet (15.2 m). She had a draught of 15 feet 9 inches (4.8 m) forward and 17 feet 4 inches (5.3 m) aft. Penelope displaced 4,394 long tons (4,465 t) and had a tonnage of 3,096 tons burthen. She had a complement of 350 officers and ratings. She was also the first British capital ship to be fitted with a washroom.

Penelope had a pair of Maudslay three-cylinder, horizontal-return, connecting-rod steam engines, each driving a single 14-foot (4.3 m) propeller. The engines used steam provided by four boilers with a working pressure of 30.5 psi (210 kPa; 2 kgf/cm2). The ship reached a speed of 12.76 knots (23.63 km/h; 14.68 mph) from 4,703 indicated horsepower (3,507 kW) during her sea trials on 1 July 1868. She carried a maximum of 500 tons of coal, enough to steam 1,360 nautical miles (2,520 km; 1,570 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph).

The shallow-draught requirement forced Barnaby to build her with twin screws, as a single screw of larger diameter would have been mounted insufficiently deep to be effective. The Admiralty also wanted hoistable propellers as the reports from Pallas and Favorite, with their fixed propellers, were distinctly uncomplimentary about their sailing qualities. She was the only twin-screw ship ever to have hoisting screws. Provision for the hoisting frames and twin rudders forced a very unusual shape to the stern, which unintentionally greatly increased drag. The other issue was that the shallowness of her draught made her very unhandy under sail, and she was described as "drifting to leeward in a wind like a tea tray". Penelope was ship-rigged with three masts and a sail area of 18,250 square feet (1,695 m2). Her speed under sail alone was only 8.5 knots (15.7 km/h; 9.8 mph). Her shallow draught gave her a metacentric height of 2.7 feet (0.8 m) at deep load, which made her a very steady gun platform.

Penelope's main armament of eight rifled muzzle-loading (RML) 8-inch (203 mm) guns was concentrated amidships in a box battery. The guns at the corners of the battery were given additional gun ports, embrasured into the sides of the hull, to give her a limited amount of end-on fire. The shell of the 8-inch gun weighed 175 pounds (79.4 kg) and was rated with the ability to penetrate 9.6 inches (244 mm) of wrought-iron armour. The ship mounted three rifled breech-loading (RBL) 5-inch (127 mm) Armstrong guns as chase guns, one in the stern and two under the forecastle in the bow, although these were judged to be very ineffective weapons. She also carried a pair of RBL 20-pounder 3.75-inch (95 mm) Armstrong saluting guns.

The waterline wrought iron armour belt of Penelope covered her entire length. It was 6 inches (152 mm) thick amidships, backed by 10–11 inches (254–279 mm) of wood, and thinned to 5 inches towards the ends of the ship. It had a total height of 5 feet 6 inches (1.7 m), of which 4 feet (1.2 m) was below water and 1 foot 6 inches (0.5 m) above. The sides of the 68-foot-long (20.7 m) box battery were also 6 inches thick, and its ends were protected by 4.5-inch (114 mm) bulkheads. Between the battery and the belt was a 96-foot-long (29 m) strake of 6-inch armour, also closed off by 4.5-inch bulkheads.[3]

Construction and career

Penelope, named after the wife of Odysseus, was the fifth ship of her name to serve in the Royal Navy. She was ordered in February 1865 and was the first iron-hulled ship to be built at Pembroke Dockyard. The ship was laid down on 4 September and was launched by the wife of the new captain-superintendent of the dockyard, Captain Robert Hall, on 18 June 1867.

Penelope was completed at Devonport Dockyard on 27 June 1868 for the cost of £196,789 and served in the Channel Fleet until June 1869. She was then guard ship at Harwich until 1882, which included summer cruises in company with the rest of the reserve fleet. On 7 January 1876, the German merchant ship Victoria ran into her at Harwich, causing minor damage. She was part of the Particular Service Squadron mobilised during the Russian war scare of June–August 1878. On 18 January 1881, she was driven from her moorings at Harwich and ran aground in the River Stour.

In 1882, she was at Gibraltar under command of Captain St George Caulfield D'Arcy-Irvine when the Anglo-Egyptian War began, and her shallow draught caused her to be sent to Egypt. Upon arrival in Alexandria, she assisted with the evacuation of European refugees for several days before the bombardment of the city began on 11 July. Penelope was the ship closest to the Egyptian forts and fired 231 rounds during the battle. The ship was only lightly damaged by Egyptian shells, with eight men wounded, one eight-inch gun damaged and one main-yard needing to be replaced. She became Rear-Admiral Anthony Hoskins's flagship when the British seized the Suez Canal to allow their troop transports to land at Ismailia.

On 11 March 1883, Penelope was run into by the steam collier Dunelm at Sheerness, sustaining minor damage. Penelope returned home after the war for a further five years' service at Harwich. She was paid off in 1887, refitted, and sent to Simonstown, South Africa, as a receiving ship the following year. In January 1897, Penelope was converted to a prison hulk and then sold for scrap on 12 July 1912 for the price of £1,650. The ship was broken up at Genoa, Italy, in 1914.

She was designed for inshore work with a shallow draught, which severely compromised her performance under sail. Completed in 1868, the ship spent the next year with the Channel Fleet before she was assigned to the First Reserve Squadron in 1869 and became the coast guard ship for Harwich until 1887. Penelope was mobilised as tensions with Russia rose during the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78 and participated in the Bombardment of Alexandria during the Anglo-Egyptian War of 1882. The ship became a receiving ship in South Africa in 1888 and then a prison hulk in 1897. She was sold for scrap in 1912.

Design

The chief constructor, Sir Edward Reed, was ill, so the design of this ship was entrusted to his assistant and brother-in-law, Nathaniel Barnaby, himself a future chief constructor. For reasons that have not survived, the Admiralty required that Penelope to be a ship of unusually shallow draught, possibly in light of the operations in the shallow Baltic Sea during the Crimean War of 1854–1855.

The ship was 260 feet (79.2 m) long between perpendiculars and had a beam of 50 feet (15.2 m). She had a draught of 15 feet 9 inches (4.8 m) forward and 17 feet 4 inches (5.3 m) aft. Penelope displaced 4,394 long tons (4,465 t) and had a tonnage of 3,096 tons burthen. She had a complement of 350 officers and ratings. She was also the first British capital ship to be fitted with a washroom.

Penelope had a pair of Maudslay three-cylinder, horizontal-return, connecting-rod steam engines, each driving a single 14-foot (4.3 m) propeller. The engines used steam provided by four boilers with a working pressure of 30.5 psi (210 kPa; 2 kgf/cm2). The ship reached a speed of 12.76 knots (23.63 km/h; 14.68 mph) from 4,703 indicated horsepower (3,507 kW) during her sea trials on 1 July 1868. She carried a maximum of 500 tons of coal, enough to steam 1,360 nautical miles (2,520 km; 1,570 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph).

The shallow-draught requirement forced Barnaby to build her with twin screws, as a single screw of larger diameter would have been mounted insufficiently deep to be effective. The Admiralty also wanted hoistable propellers as the reports from Pallas and Favorite, with their fixed propellers, were distinctly uncomplimentary about their sailing qualities. She was the only twin-screw ship ever to have hoisting screws. Provision for the hoisting frames and twin rudders forced a very unusual shape to the stern, which unintentionally greatly increased drag. The other issue was that the shallowness of her draught made her very unhandy under sail, and she was described as "drifting to leeward in a wind like a tea tray". Penelope was ship-rigged with three masts and a sail area of 18,250 square feet (1,695 m2). Her speed under sail alone was only 8.5 knots (15.7 km/h; 9.8 mph). Her shallow draught gave her a metacentric height of 2.7 feet (0.8 m) at deep load, which made her a very steady gun platform.

Penelope's main armament of eight rifled muzzle-loading (RML) 8-inch (203 mm) guns was concentrated amidships in a box battery. The guns at the corners of the battery were given additional gun ports, embrasured into the sides of the hull, to give her a limited amount of end-on fire. The shell of the 8-inch gun weighed 175 pounds (79.4 kg) and was rated with the ability to penetrate 9.6 inches (244 mm) of wrought-iron armour. The ship mounted three rifled breech-loading (RBL) 5-inch (127 mm) Armstrong guns as chase guns, one in the stern and two under the forecastle in the bow, although these were judged to be very ineffective weapons. She also carried a pair of RBL 20-pounder 3.75-inch (95 mm) Armstrong saluting guns.

The waterline wrought iron armour belt of Penelope covered her entire length. It was 6 inches (152 mm) thick amidships, backed by 10–11 inches (254–279 mm) of wood, and thinned to 5 inches towards the ends of the ship. It had a total height of 5 feet 6 inches (1.7 m), of which 4 feet (1.2 m) was below water and 1 foot 6 inches (0.5 m) above. The sides of the 68-foot-long (20.7 m) box battery were also 6 inches thick, and its ends were protected by 4.5-inch (114 mm) bulkheads. Between the battery and the belt was a 96-foot-long (29 m) strake of 6-inch armour, also closed off by 4.5-inch bulkheads.[3]

Construction and career

Penelope, named after the wife of Odysseus, was the fifth ship of her name to serve in the Royal Navy. She was ordered in February 1865 and was the first iron-hulled ship to be built at Pembroke Dockyard. The ship was laid down on 4 September and was launched by the wife of the new captain-superintendent of the dockyard, Captain Robert Hall, on 18 June 1867.

Penelope was completed at Devonport Dockyard on 27 June 1868 for the cost of £196,789 and served in the Channel Fleet until June 1869. She was then guard ship at Harwich until 1882, which included summer cruises in company with the rest of the reserve fleet. On 7 January 1876, the German merchant ship Victoria ran into her at Harwich, causing minor damage. She was part of the Particular Service Squadron mobilised during the Russian war scare of June–August 1878. On 18 January 1881, she was driven from her moorings at Harwich and ran aground in the River Stour.

In 1882, she was at Gibraltar under command of Captain St George Caulfield D'Arcy-Irvine when the Anglo-Egyptian War began, and her shallow draught caused her to be sent to Egypt. Upon arrival in Alexandria, she assisted with the evacuation of European refugees for several days before the bombardment of the city began on 11 July. Penelope was the ship closest to the Egyptian forts and fired 231 rounds during the battle. The ship was only lightly damaged by Egyptian shells, with eight men wounded, one eight-inch gun damaged and one main-yard needing to be replaced. She became Rear-Admiral Anthony Hoskins's flagship when the British seized the Suez Canal to allow their troop transports to land at Ismailia.

On 11 March 1883, Penelope was run into by the steam collier Dunelm at Sheerness, sustaining minor damage. Penelope returned home after the war for a further five years' service at Harwich. She was paid off in 1887, refitted, and sent to Simonstown, South Africa, as a receiving ship the following year. In January 1897, Penelope was converted to a prison hulk and then sold for scrap on 12 July 1912 for the price of £1,650. The ship was broken up at Genoa, Italy, in 1914.

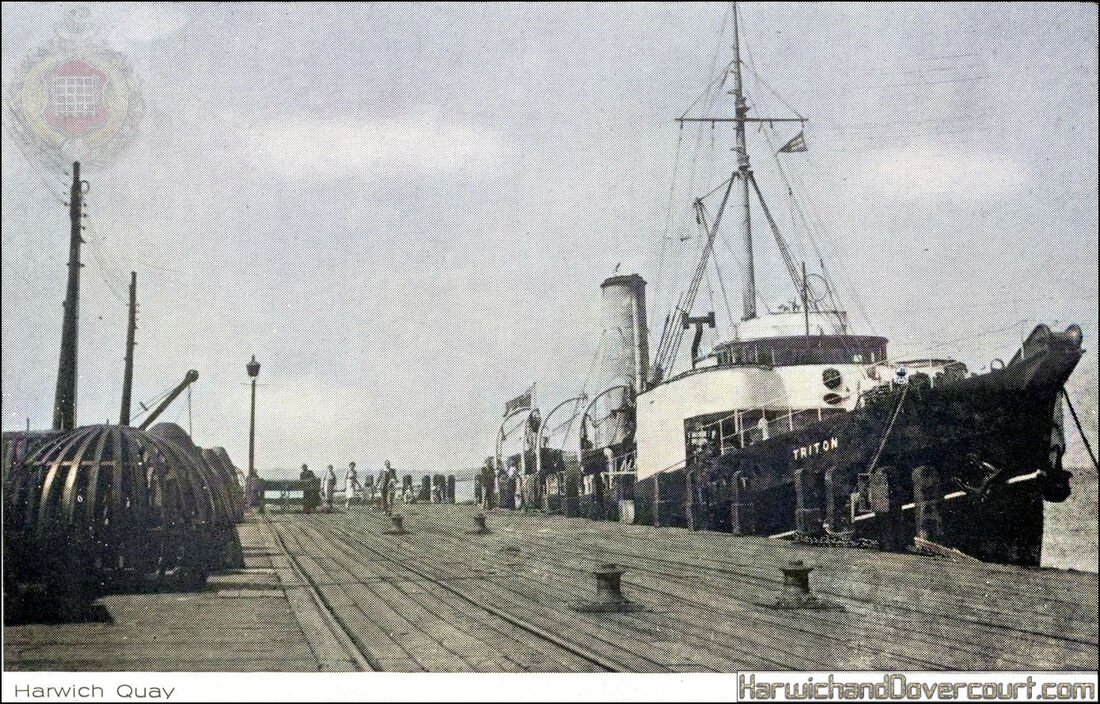

~ The Triton at Harwich Quay (1955) H&D ~

Trinity House Pier at Harwich. Tender Triton on the right

Trinity House tender Triton. She was ordered as a trawler and launched on 19th August 1939 as Queen of the Waves at Goole. Trinity House purchased the vessel whilst still under construction, had her converted into a tender sailing from Goole to Harwich on 31st August 1940 where she remained based until sold for breaking up in 1963

Trinity House tender Triton. She was ordered as a trawler and launched on 19th August 1939 as Queen of the Waves at Goole. Trinity House purchased the vessel whilst still under construction, had her converted into a tender sailing from Goole to Harwich on 31st August 1940 where she remained based until sold for breaking up in 1963

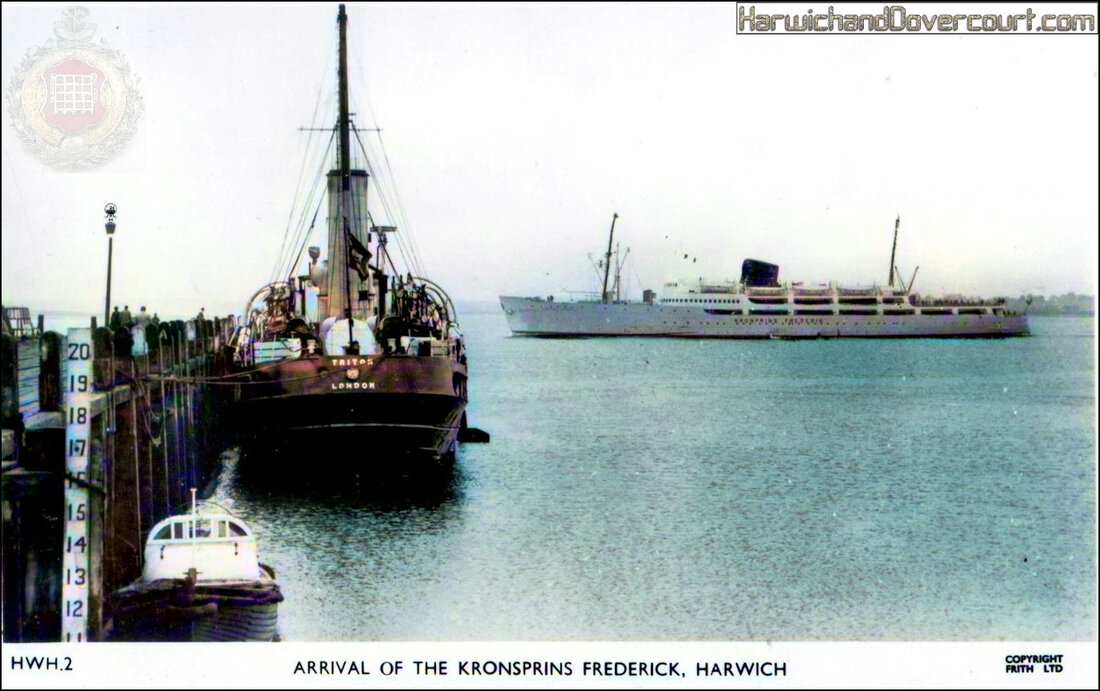

~ Arrival of the Kronsprins , Frederick Harwich (1959) Frith's H&D ~

Trinity House Pier at Harwich. Tender Triton on the left